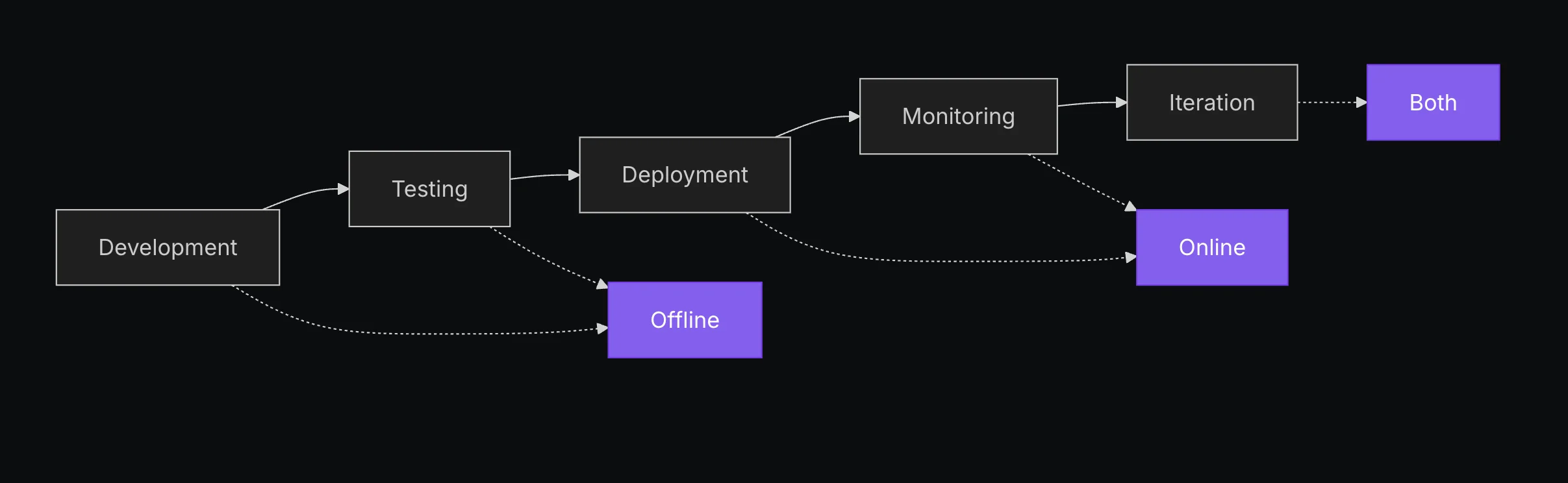

The proliferation and discovery of AI applications in recent years has challenged traditional software engineering lifecycles. We've all seen by now the headline stat that 95% of generative AI pilots at companies are failing, but why is this the case and how does one position oneself in the successful 5%?

First, let's talk about the proliferation. The barrier to create AI applications has rapidly decreased with the introduction of LLM-based coding assistants, allowing for a multitude of niche, custom tooling to be built to support any manner of workflow desired. While incredible, this creates the situation where the cost of building proof of concepts is generally free, but actually productionizing and full adoption remain difficult. Initial responses from LLM PoCs can get us roughly 60-70% of the way there with limited effort, providing an inclination that an idea can work. This leads to investing time in a little more prompt engineering- trying out a few more test cases to boost our responses to 80% satisfaction. But, as with all PoCs (yet amplified by the ease and behavior of LLMs), the remaining 20% is where the bulk of the work lands.

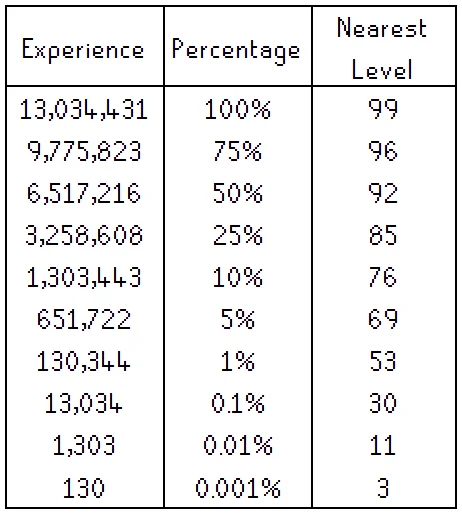

In the classic game Old School RuneScape, reaching level 92 in a skill meant you had 50% of the XP required to reach 99.

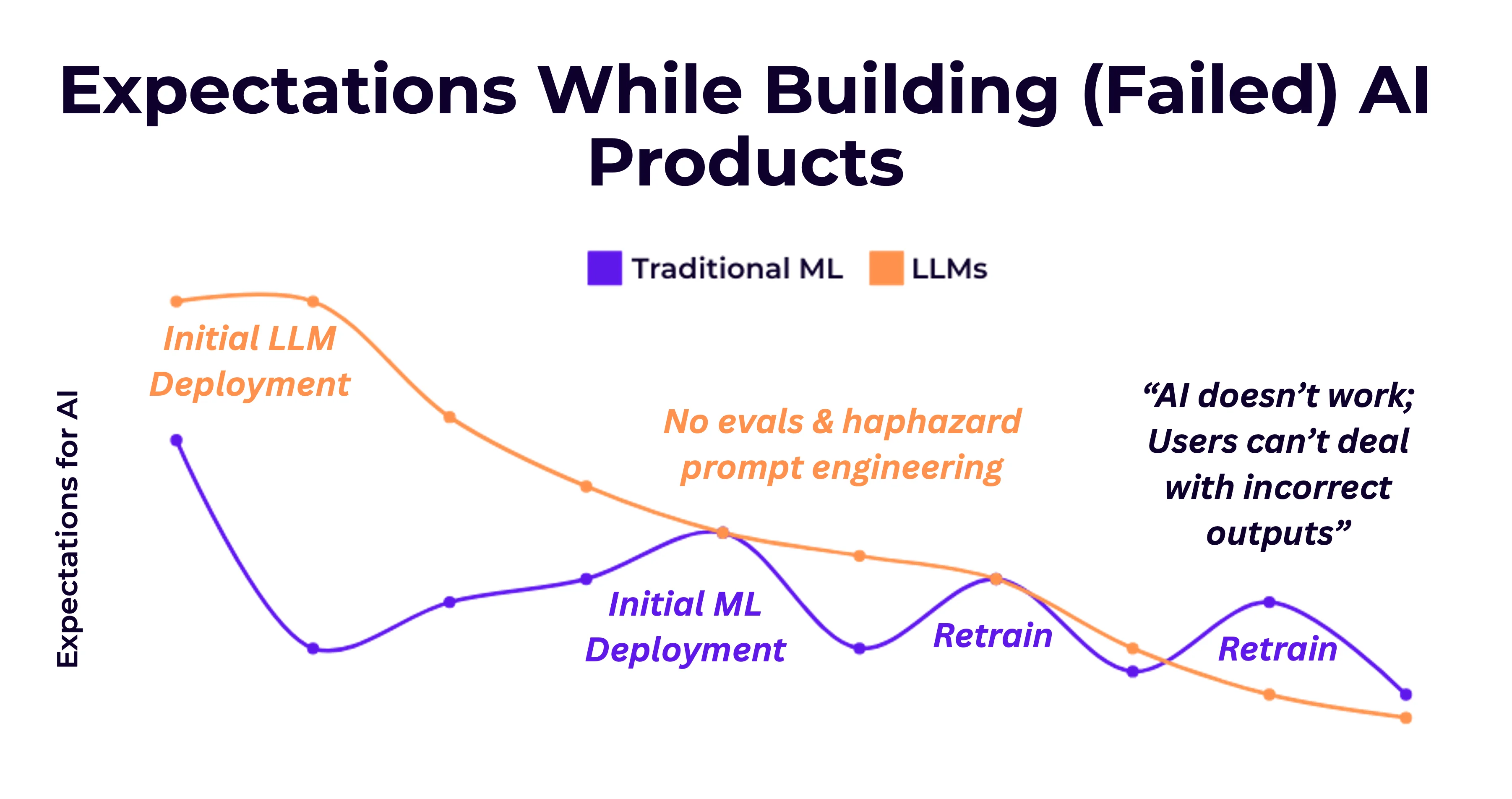

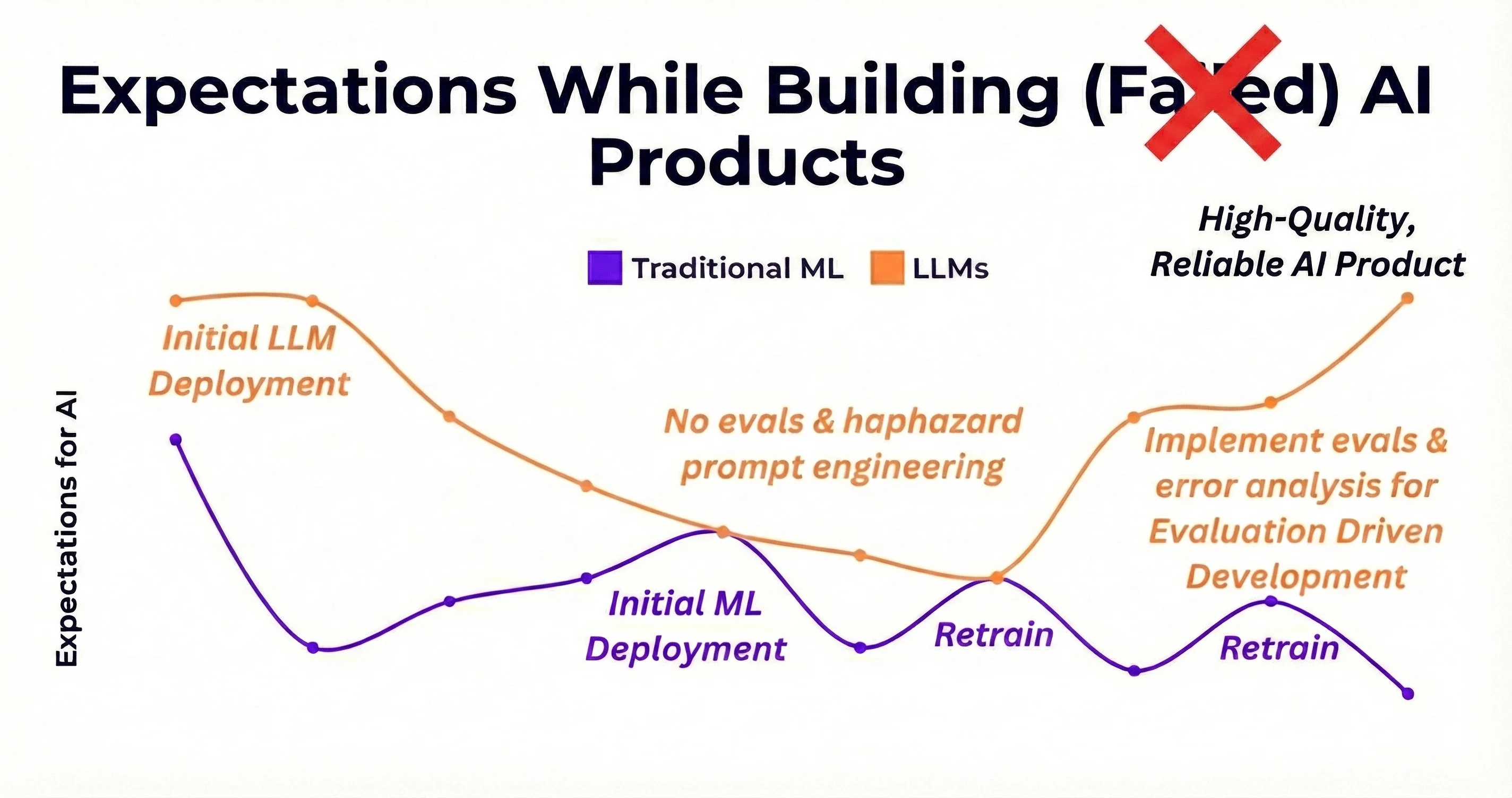

Even if a PoC does make it to deployment, expectations can fall short of initial promises. As Shreya Shankar states in her blog Short Musings on AI Engineering and "Failed AI Projects":

"Teams often expect too high of accuracy or alignment with their expectations from an AI application right after it’s launched, and often don’t build out the infrastructure to continually inspect data, incorporate new tests, and improve the end-to-end system"

Which ultimately leads to eroding trust in your system and software from your stakeholders and end users. Not the goal! The solution, then, is to consider how to build systems that do support measurement and improvement.

Looking into this surfaces an important distinction between traditional and AI (primarily LLM-based) software testing. In regular software engineering, we employ unit/integration tests, quality assurance, and user acceptance testing on deterministic outcomes, covering edge cases and user preferences in a repeatable and deterministic manner. In contrast, LLM behavior and output are, by nature, stochastic and subjective. No two runs will be the same and the output generated or actions taken are thus difficult to quantify and measure. We run into a situation of trying to define success, when success itself can contain multiple states and is largely unknown. A response will look different every single time when generated independently from an LLM, but all can be equally beneficial or not to each user.

To properly measure and improve, we need to do three things:

- Define our metrics alongside development

- Transition our evaluation and success metrics from technical to user-centric measurement

- Look more at the trajectory (often referred to as the trace) of the AI system

On the third point, getting to a final output from an LLM system requires many different non-deterministic systems to interact with each other at varying levels of complexity. What may constitute 'bad output' to a user could be attributed to any of:

- The LLM's core reasoning and intent understanding

- Tool selection and parameterization

- Tool response observation and interpretation

- Retrieval or context system performance

- Agent-to-agent interpretation

- The opinion of the user reading the output

- The user's trust in the system as a whole

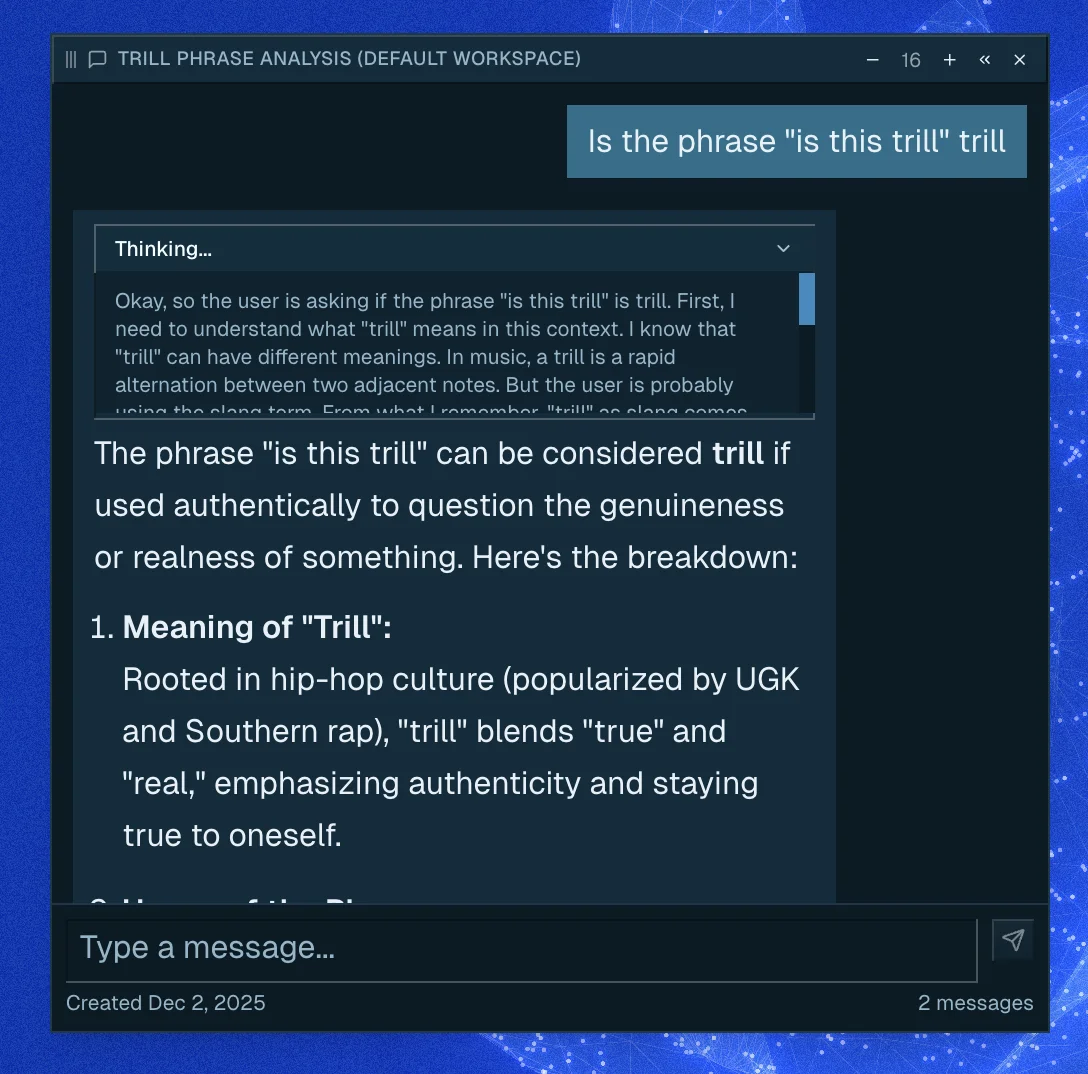

So on and so forth. LLMs' inherent operational style of reasoning, planning, and acting is both what makes them incredibly capable and useful, yet infinitely tricky to achieve reliable performance. Guiding and working with LLMs is often compared to having a very capable intern who is eager and knowledgeable but requires oversight for following expected processes and producing expected deliverables. In more ways than one, evaluating LLM products looks similar to assessing a person- "Do they understand the task?", "Do they take the right steps?", "Do they come to a conclusion in an efficient manner?", "Do they have the right tools and resources?", "Is the quality of their work as expected?"...

Which brings us to our second point, to do this measurement effectively we must fundamentally change how we evaluate.

Common evaluation metrics like p95 response time, requests per second, cache hit rates, and similar metrics give us great information about system performance, but they fail to surface anything related to the actual quality of LLM performance. Put more bluntly from Google's whitepaper on Agent Quality:

Traditional software verification asks: “Did we build the product right?” It verifies logic against a fixed specification. Modern AI evaluation must ask a far more complex question: “Did we build the right product?”

For this, we must define success not at a deeply technical level, but at a user-centric level. In other words, to improve AI behavior we care less about the signal of whether the system performed or not, and more about digging into the value the system provided and how that aligns with the end user's expectations.

Which is a lot easier said than done. Measuring the value of an LLM product's output and process remains subjective, application-specific, and requires additional overhead of time and resources to collect and analyze. Often we don't know exactly what to measure until we start testing and developing our product (point 1), but the payoff of this effort investment allows us to drive effective evaluation-driven development and employ AgentOps best practices by enabling rapid identification and quantification of gaps in LLM systems, helping to bring responses closer to the benefits that the end user and business expect. Let's dig into how this is done.

What Are LLM Evaluations

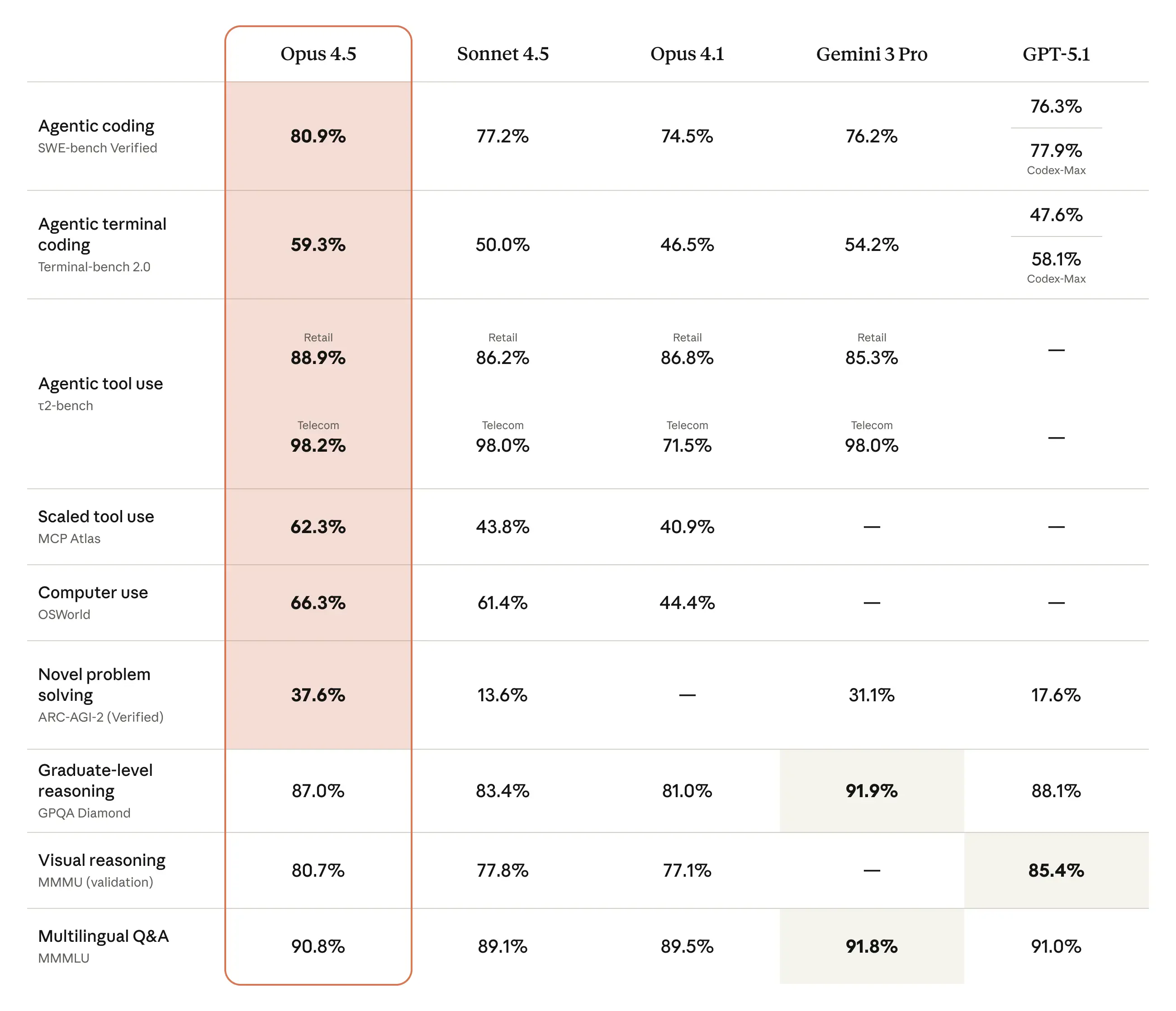

Before we get into the specifics, a few things to note. While you or a loved one may suffer from not implementing evaluations into your current LLM product, LLMs themselves have already been extensively benchmarked by their creators. You've probably seen a table that looks like the one below, packaged with every major model release from AI labs:

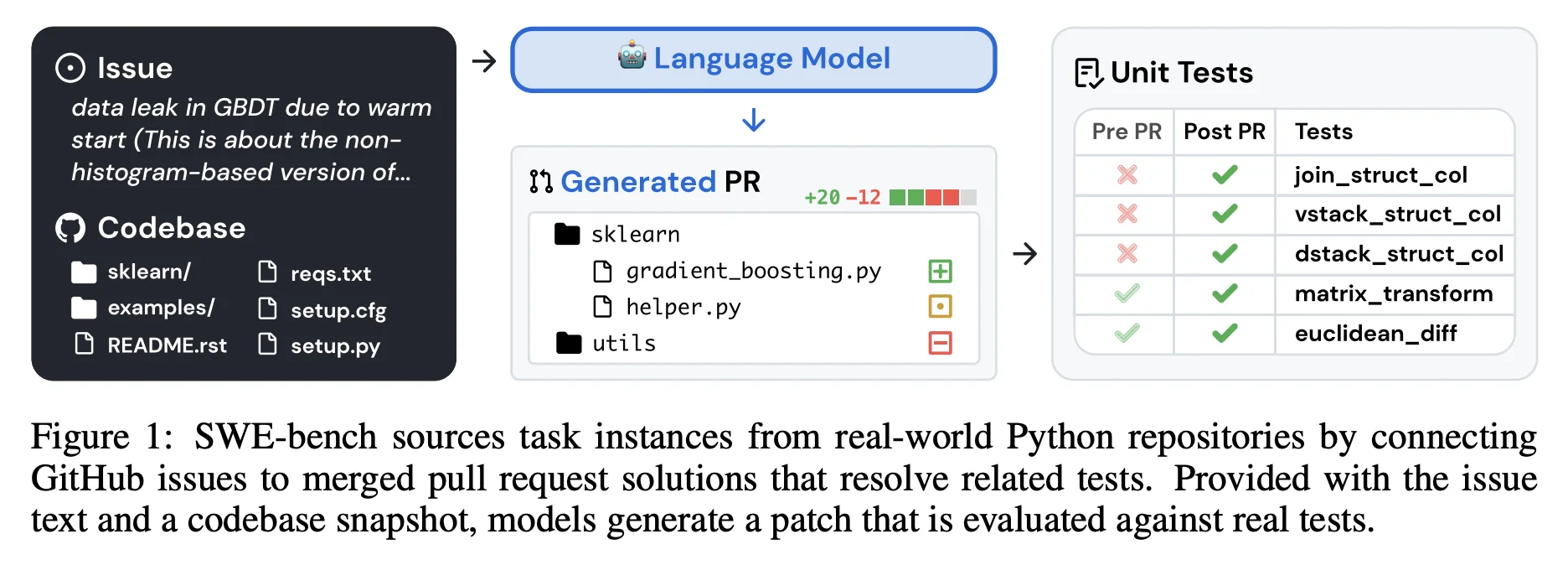

These various evaluation suites are extensively tracked during the pretraining and fine-tuning of state-of-the-art LLMs, and are able to showcase some measurable level of competency in various behaviors. Popular datasets include SWE-Bench for real world coding evaluations, GPQA for graduate level Q&A, MMMLU for multimodal multilingual understanding, etc., etc. Often wildly underappreciated and glossed over as 'unrealistic benchmarks that don't tell us real-world performance', these measurements have actually already done a lot of the hard work of making sure the reasoning engine behind your application actually works. The fact that LLMs can already follow instructions, perform robust tool calling, understand and answer difficult questions, and (especially) code well comes from the effective and successful implementation of the aforementioned measurements.

SWE-bench: Can Language Models Resolve Real-World GitHub Issues?

I, as I'm sure many others have done in the same situation, looked at these and thought "cool, but none of this actually correlates with performance in my own application." Which is, to some degree, true! But what I failed to see was the amount of time, energy, and effort that had been put into creating effective benchmarks, and how to apply similar methodology to make and apply my own.

Among most LLM application benchmarks and evaluations, there tend to be three primary types:

- Human Feedback

- LLM-As-A-Judge

- Functions

Which are all interdependent, serve various purposes along the lifecycle of evaluating and measuring LLM application performance, and evolve as the application is created. Often considered the 'gold standard', and where most domain-specific evaluations stem from, starts with gathering application-specific human feedback.

Talking to People

How do you know if someone likes what you did? You ask them! And with that simple one-step process, you've collected valuable human feedback that you can take immediate action on... sort of... but the same concepts apply when we talk about human feedback for defining evaluations. Ideally, your system already has an overarching purpose that's been surfaced through market research or defining requirement with your application stakeholders, so you should know the purpose of the system and ideal end state you're attempting to optimize towards.

For example, a flight booking agent should be able to successfully book a flight, a customer service agent should be able to effectively service the customer, a niche enterprise workflow automation agent should be able to successfully complete the step being automated.

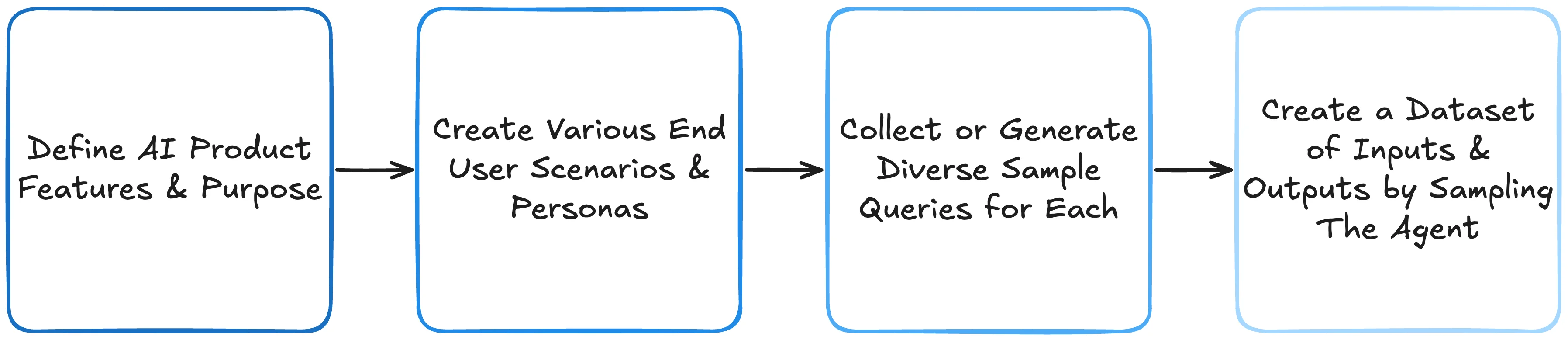

With our baseline understanding of what the system should do, we can begin to account for the various personas that will be using the product and the desired use cases it is intended to support. This can range from complex, in the case of open-ended assistants, to straightforward if only supporting a single workflow. Armed with this, we would then build out an initial "evaluation exploration" dataset. This is done by using the proof of concept's performance as a baseline for human assessment and a vehicle for determining what's useful to measure. In short, we have to observe our initial state's performance. Given the various personas and use cases, outputs and traces can be generated (either manually or synthetically) to represent a diverse set of examples. This often comes out to somewhere between 20-100 example queries as our starting inputs, run through our system, and then popped into a table of input/output pairs.

With this set comes the actual hard part, observation, and not for the reason you may think. You've probably done your fair share of data science and digging into datasets to better understand what they represent and how to harness them, but this time it's likely that you are not the authority on judging your product's success. I run into this situation all the time as an AI subject matter expert within an enterprise organization- while having the expertise and understanding of artificial intelligence is my specialty, I am not the expert on the domains it's being applied to. It is crucial that you look to the SMEs you are servicing to help guide and evaluate your product.

Given these examples created, we ask our captive domain expert to annotate and score the outputs line by line, providing their own reasoning trace and pass/fail indicator. It is suggested, at this point, to keep the scoring to a binary indicator of whether the output was good/bad, true/false, pass/fail, as our main goal is to see where the agent and the expert align or diverge before digging into specifics. Importantly, encouraging robust qualitative feedback is critical as the majority of our evaluation definitions will come from analyzing the feedback collected (even better if you can get an actual output example written by the SME for what the response should have been).

Using LLM-as-a-Judge For Evaluation: A Complete Guide

Assuming you were able to successfully trick convince your SME stakeholder to annotate your traces and provide the feedback requested, we can now begin the true evaluation definition process using a technique called error analysis. As expanded on in the many blogs of Hamel Husain (and which parallels my professional experience):

"Your evaluation strategy should emerge from observed failure patterns"

Error analysis, in a nutshell, is nothing more than looking at instances where your system fails and clustering these across common themes. These themes will become apparent as you process feedback across many different runs, as individual pain points are surfaced time and time again which become the basis for your evaluations.

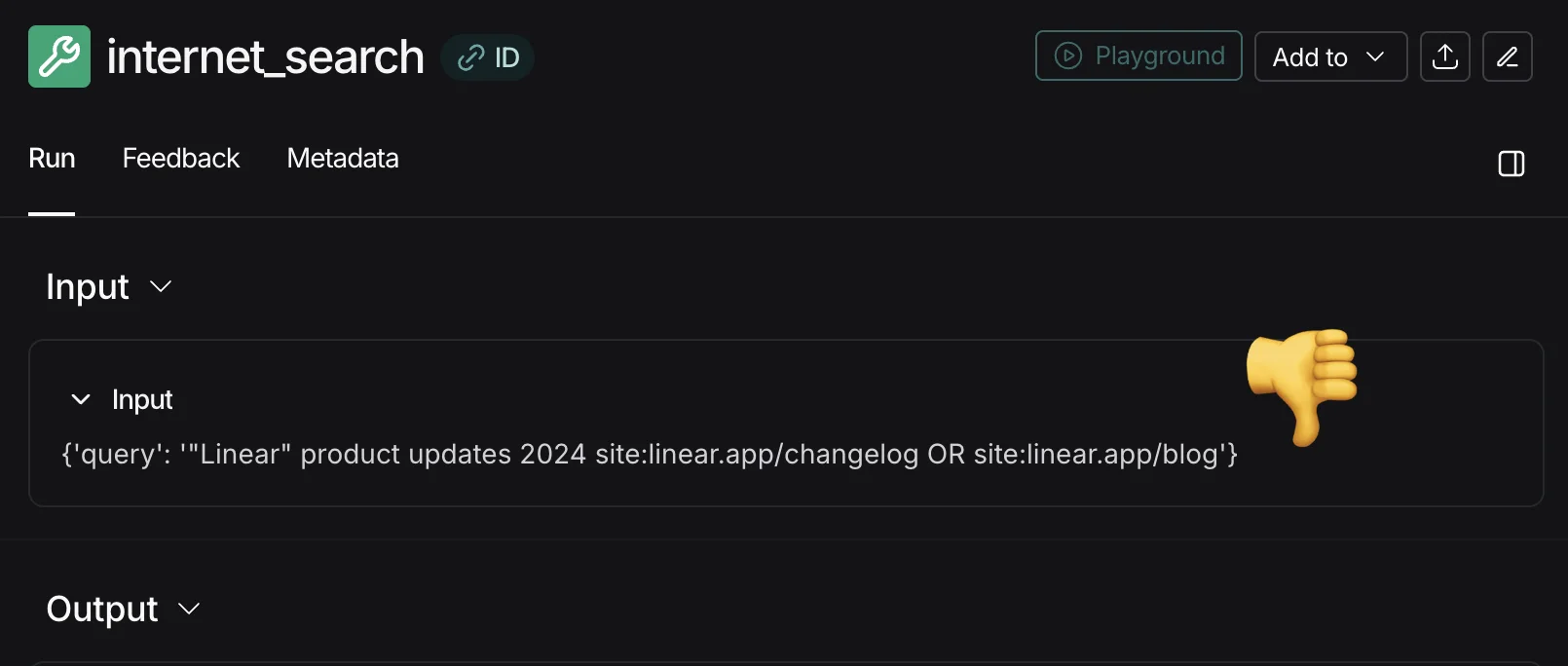

It's likely that you have already done this in some manner during initial PoC development. For example, I was recently debugging deep agent traces across 10 generated reports from my Deep Competitive Analyst and noticed the model was prompting the web search tool like a SERP API, whereas best practices for the specific API were just to query in natural language. This behavior led to a diminished quality of results returned and propagated inefficiencies downstream. It was only through observing and analyzing where the system output failed (mediocre report citations) that I could identify the cause (function call parameterization) across the runs. I then noted that a specific evaluation to measure for my application would be adherence to the search tool's expected query style, or more broadly for the final output: relevance of citations.

It's this style of analysis that we're looking to do to define what performance or behaviors are useful to monitor and assess. Notably, a phenomenon exists regarding defining evaluations, coined criteria drift:

"We observed a 'catch-22' situation: to grade outputs, people need to externalize and define their evaluation criteria; however, the process of grading outputs helps them to define that very criteria. We dub this phenomenon criteria drift, and it implies that it is impossible to completely determine evaluation criteria prior to human judging of LLM outputs."

Who Validates the Validators? Aligning LLM-Assisted Evaluation of LLM Outputs with Human Preferences

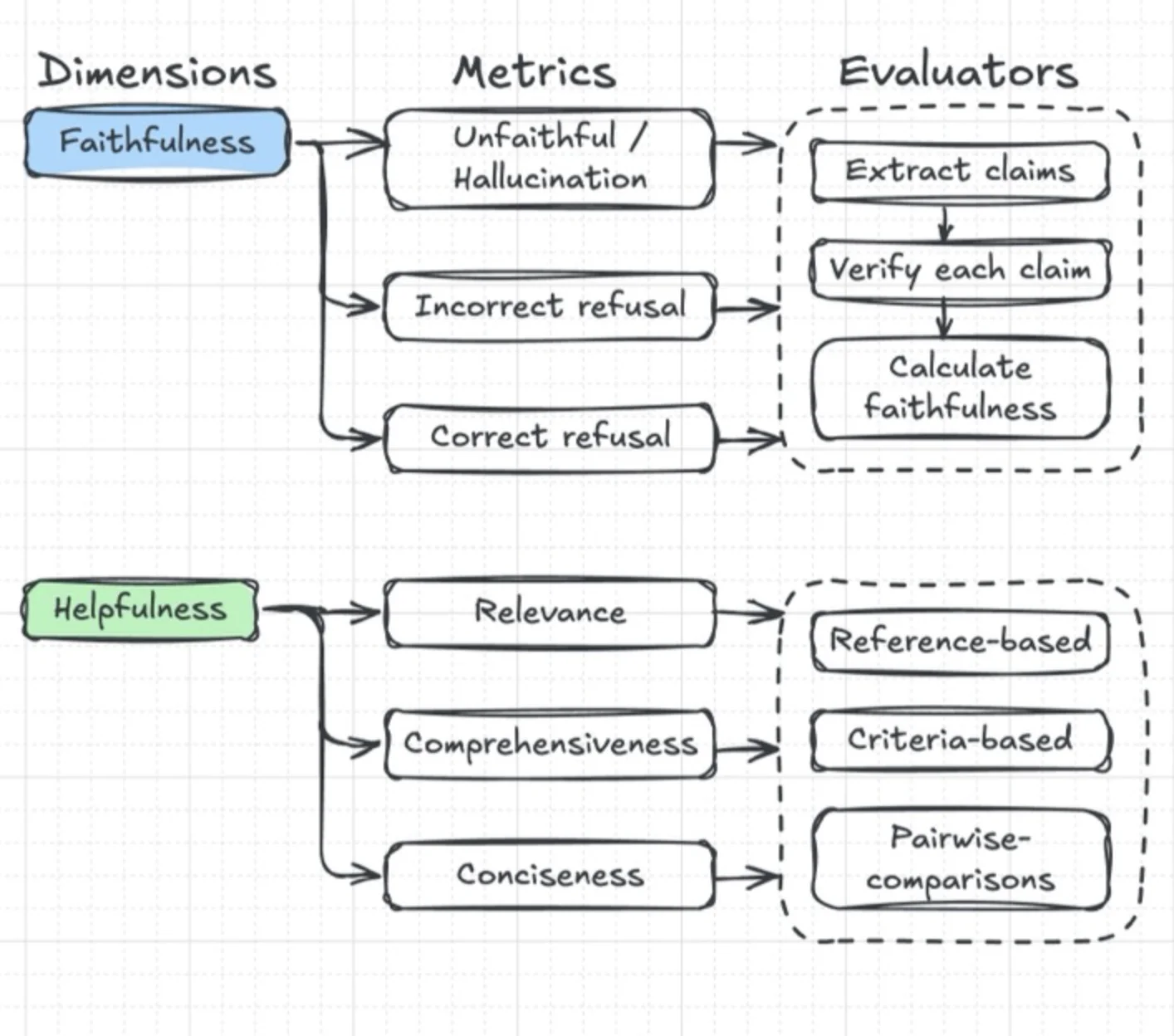

Teams often make the mistake of defining evaluations much too early, looking at generic definitions of "helpfulness", "hallucination rate", "tone", etc., before applying them. While these generic metrics come from valid and existing methodology of evaluation-

Evaluating Long-Context Question & Answer Systems

off-the-shelf definitions often lack the specificity and application to your own product. However, through this generation, annotation, and observation cycle, we can then begin to group similar failures together to categorize failure modes, which become our candidates and definitions for product specific evaluations.

To summarize, running this annotation and generic scoring exercise should allow us to surface the various failures of our system, how they are grouped, and thus identify areas for improvement and evaluation. We also assume that optimizing for these metrics will be an effective use of our time, as they are what's been identified as critical and important to the SME (whose opinion we extend as our best indicator of what would be beneficial for the masses). It additionally allows us to immediately address any glaring issues in our LLM behavior that can be fixed with a prompt update. As a rule of thumb, if a quick fix can address a problem, then the extra effort to build an evaluation for that failure isn't necessary; any issues that persist through a hotfix will remain our candidate metrics to measure.

At this point, it's useful to move to a second exercise of generated outputs and annotation, this time by adding pass/fail labels for the surfaced and newly defined eval metrics. See the following example of this, again from Who Validates the Validators?:

The reasons for this are twofold: first, it provides a baseline of human judgment (our gold standard!), and second, it lets us surface any additional criteria that may emerge from an additional review.

By this point, the SME you're working with is probably tired, hates you, hates annotating, and has more important things that they've started doing instead (if they haven't already). This is where we scale the human annotation process using AI itself, in a technique you certainly saw coming called LLM-as-a-judge.

LLM-As-A-Judge-Jury-And-Executioner

LLM-as-a-judge offers us the following benefit: scaling human feedback while not needing humans. For the uninitiated, LLM-as-a-judge consists of asking an LLM to provide some form of feedback on an output based on some defined criteria. The LLM will then perform its observation (and optional reasoning), outputting written feedback or a scalar/binary score. As you can tell, this is meant to do the same actions as our human annotator, automated.

However, a few initial pitfalls exist with naive implementation:

- Loosely Defined Criteria: Providing poorly structured criteria to judge, i.e., saying "Rate how helpful this is" without defining what helpful means for your application leads to inconsistent (and unhelpful) scoring.

- Weak Models: Using cheap, small, or low-cost models often correlates with inconsistent and worse performance. You want to use the smartest and most capable model you can afford.

- Scalar Scoring: Prompting models to output scores on a scale often fails to produce accurate distributions. Humans themselves can barely define the difference between a 3/5 and a 4/5. We understand a lot better when something succeeds vs fails.

I often see teams jump straight to this step, implement a few useless LLM-as-a-judge evaluators, never get anything useful or actionable from their irrelevant scores, and give up. This is why we do all the pre-work in the human feedback section to surface, define, and baseline relevant evaluations. On top of all the articulated benefits, it gives us the foundation to align LLM judges to our human performance so we can automate and scale scoring. If you thought we were done defining, then think again- we're just getting started with meta-evaluations!

An LLM-as-Judge Won't Save The Product—Fixing Your Process Will

But this time we can use some classic metrics to assess the model's performance versus the humans. It is recommended at this stage to have a good mix of failures and passes across your metrics to ensure your LLM judge can catch both modes, and then create an individual prompt for each evaluation metric. While it may be tempting to have one single prompt to assess output across multiple dimensions, in practice we can get much better results when focusing and optimizing judge prompts for single evaluations. It's also exponentially more difficult to optimize the judge prompt, as a tweak here may improve one dimension while degrading another. So, for all humans and AI involved, keep each independent. Upon running your prompts through and parsing the scores, we can then use various agreement and classification performance metrics to assess alignment. One of the most popular here is Cohen's κ, which measures inter-rater agreement while correcting for chance agreement. Its equation comes out to: \(κ = \frac{p_o - p_e}{1 - p_e}\)

where:

- \(p_o\) represents Observed Agreement: \(p_o = \frac{TP + TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN}\)

- \(p_e\) represents Expected Agreement: \(p_e = \frac{(TP + FP)(TP + FN)}{N^2} + \frac{(TN + FN)(TN + FP)}{N^2}\)

Which outputs a value between -1 and 1. Cohen's κ has a conservative interpretation, where what looks like a middle-of-the-road score is actually a good indicator of agreement. We interpret this as:

| κ range | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| ~0.0 | No better than chance |

| 0.2–0.4 | Fair agreement |

| 0.4–0.6 | Moderate agreement |

| 0.6–0.8 | Substantial agreement |

| 0.8+ | Almost perfect agreement |

It's rare that two humans agree perfectly, so getting at least substantial agreement (κ > 0.6) with an aligned LLM judge tends to be adequate for most evaluations. For high-stakes applications (safety, medical, legal), you may want to target κ > 0.8.

Under our assumption of the human label as ground truth and calculating our true/false positives/negatives, we can also compute standard classification performance metrics:

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | \(\frac{TP + TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN}\) | Overall correctness across all predictions |

| Precision | \(\frac{TP}{TP + FP}\) | When LLM says pass, how often is it right? |

| Recall | \(\frac{TP}{TP + FN}\) | Of actual passes, how many does LLM catch? |

| F1 Score | \(\frac{2 \times \text{Precision} \times \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}}\) | Single score balancing precision and recall |

| Specificity | \(\frac{TN}{TN + FP}\) | Of actual fails, how many does LLM identify? |

Since these are relatively easy to compute with our binary scores, it's straightforward to iterate on LLM judge prompts, run experiments, and measure improvement or regression. You can employ your best prompt engineering skills here to achieve alignment, add in few-shot examples, show example annotations, experiment with prompt optimizers (to be discussed), etc. Do what works for you until you have a sufficiently trained judge; repeat for each dimension of your total evaluation rubric.

Harnessing the reasoning power of LLMs can help provide quantitative scores for more complex evaluations, but you don't necessarily need to use an LLM for all your scoring. Simpler or more straightforward tests can still be good ol' fashioned functions.

Back to Tests

When considering implementations for evaluations, it can be easy to overcomplicate things by jumping to an LLM judge experience, but I beg you to pause for a minute to consider whether there are easier ways to assert your criteria. For example, checking for proper link citation, whether an expected subject is referenced or not, or the existence of a code block can all be done with a quick regex function.

import re

def eval_link_formatting(text: str) -> bool:

"""Fail if any URLs exist outside proper markdown format."""

# Find all URLs anywhere in text

all_urls = re.findall(r'https?://[^\s\)]+', text)

# Find URLs inside valid markdown links

valid_pattern = r'\[([^\]]+)\]\((https?://[^\)]+)\)'

valid_urls = [url for _, url in re.findall(valid_pattern, text)]

if not all_urls:

return True

return len(all_urls) == len(valid_urls)I also consider some functions as a quantitative proxy for human preferences. Verbosity levels can be approximated via a len() check or engagement and tone through counts of exclamations or first/second pronoun ratios, to name some examples. I've also seen semantic similarity applied to check if outputs are similar to retrieved documents in Q&A tasks to give an indication of how 'on topic' a response is. A word of warning: as with all testing discussed, we would still want to ensure our function-based estimates are in agreement with professional opinions.

def is_impersonal(text: str) -> bool:

"""True if text favors impersonal pronouns."""

words = text.lower().split()

personal = {"i", "me", "my", "you", "your", "we", "our"}

impersonal = {"it", "one", "they", "the"}

personal_count = sum(1 for w in words if w in personal)

impersonal_count = sum(1 for w in words if w in impersonal)

return impersonal_count >= personal_countIn practice, we often use a mixture of LLM judge and function evaluations across our evaluation rubric, applying functions for straightforward and simple checks and LLMs for fuzzy or reasoning-based scoring. To call back to our search API example, I may create a function to parse and check against common SERP filtering patterns, while relying on an LLM's judgment to assess whether the query itself is high-quality.

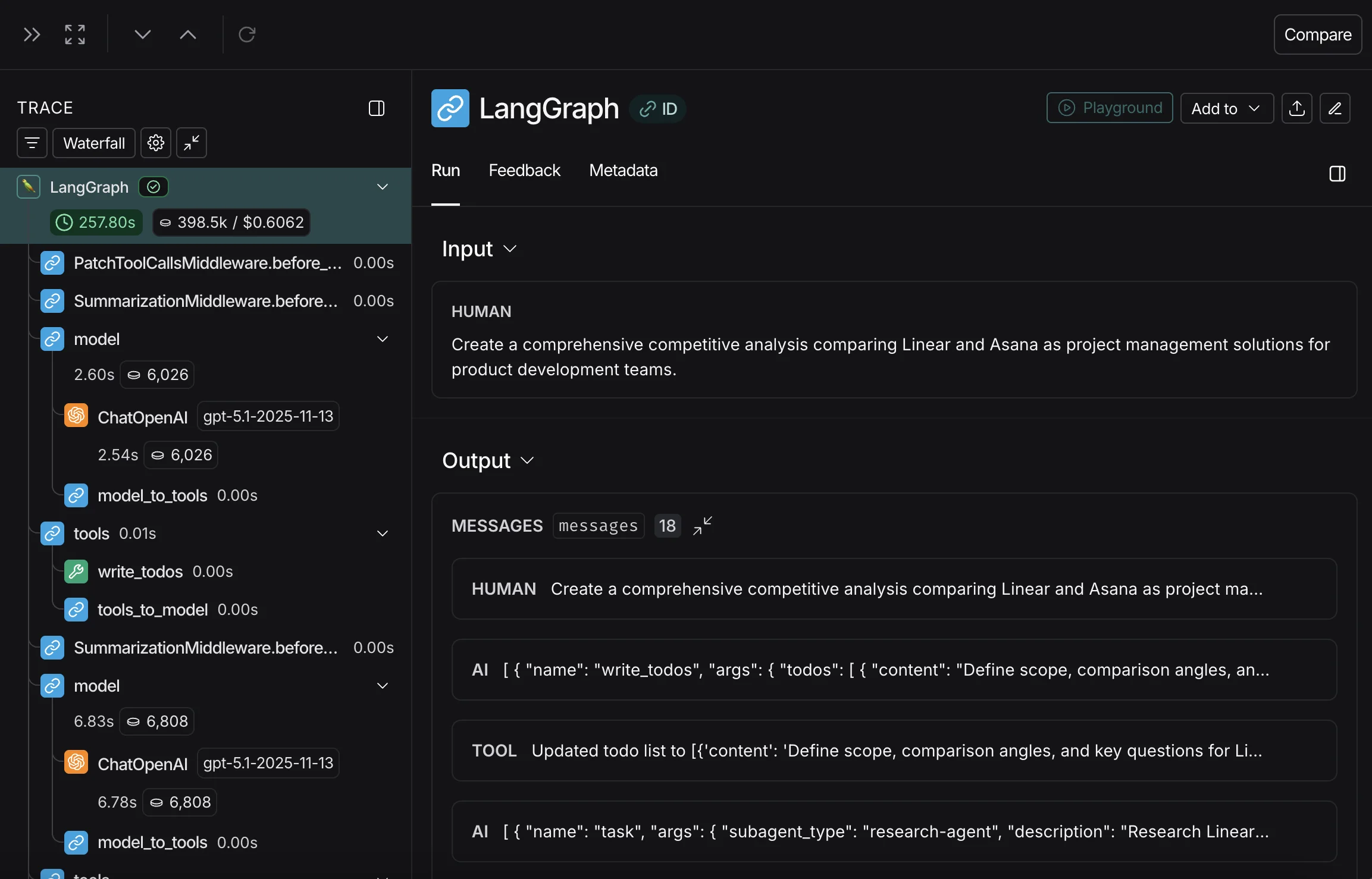

Observing the Observer

With all these various metrics, you're probably wondering what tools or platforms support running and visualizing evaluation performance. This problem is largely addressed by LLM observability platforms- the platforms that show you the full trace and step-by-step run of an application. Many different tracing and observability platforms have popped up recently, but my personal favorite of the ones I've tried has been LangChain's LangSmith. Their main concept that makes the ecosystem so smooth is that your outputs are automatically logged in your traces, and you can define and run both function and LLM-based evaluations directly in the platform. This makes it convenient for setting up both offline experiments and online monitoring; however, this does come at a monetary cost for usage and logging traces.

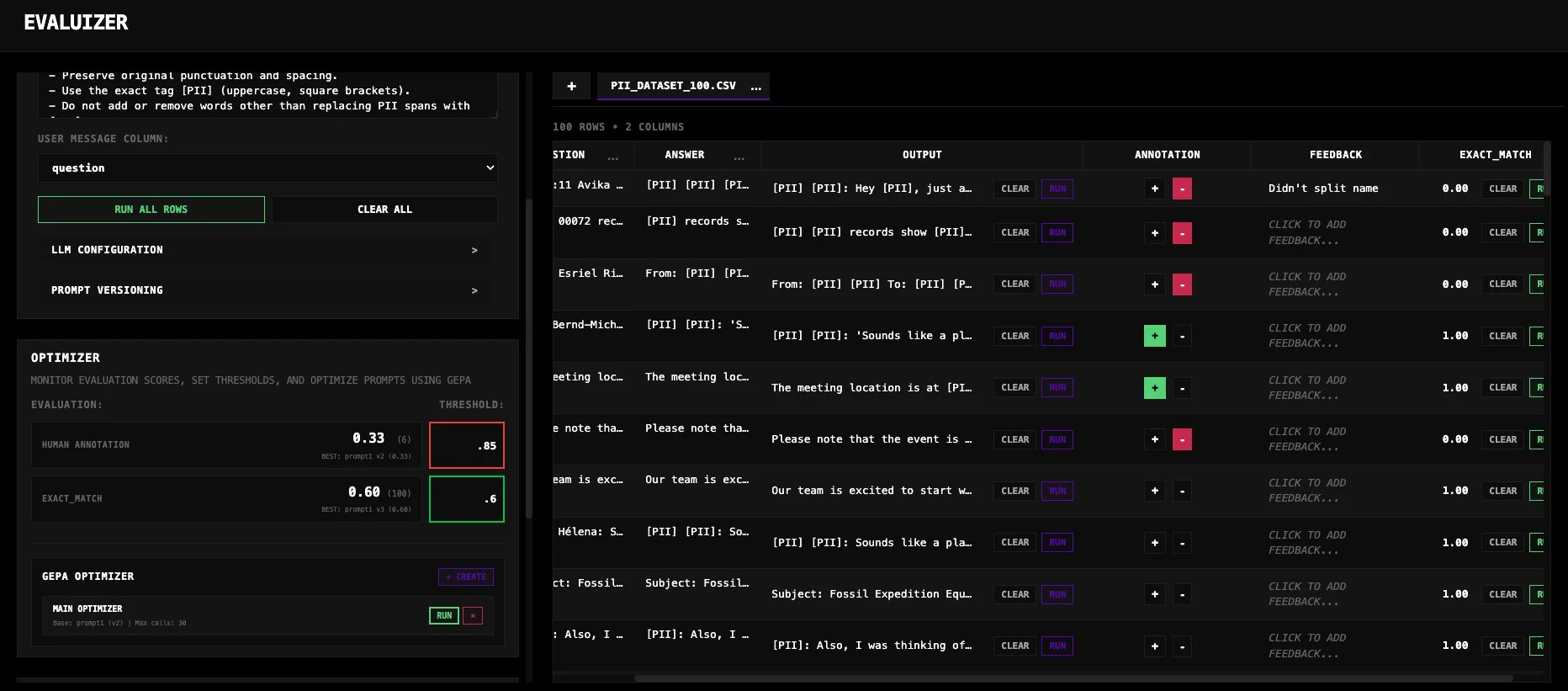

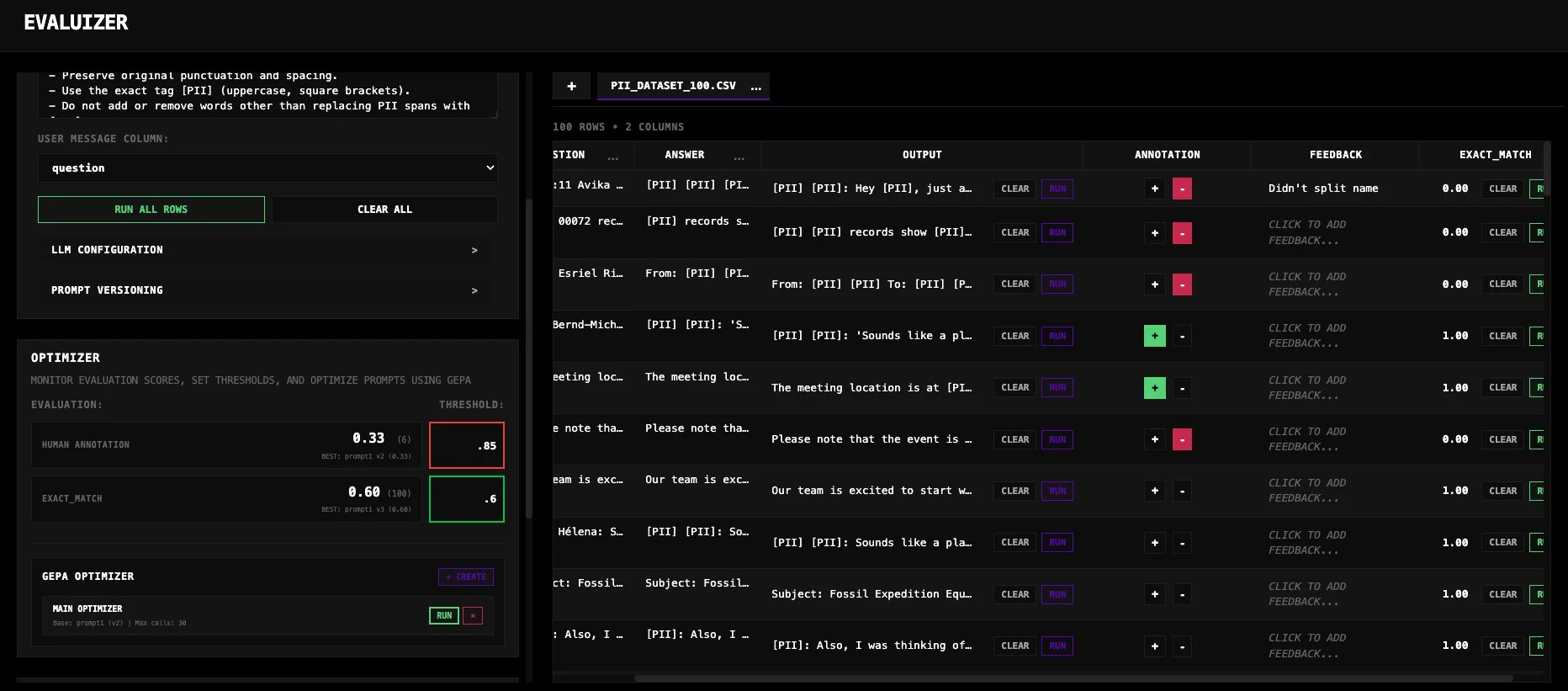

Occasionally I do find there to be a need for custom visualizations and workflows depending on how you best interact with your stakeholder team and run your experiments. No two development and business teams operate the same, nor do they generally act the same, which led me to create my own custom annotation and experiment platform Evaluizer. On top of the benefits that custom builds can bring by addressing your exact niche, I also found the exercise of creating an application like this helped me think through what tools and functionality I would need to be most effective with creating, running, and applying evaluation output to drive product improvements.

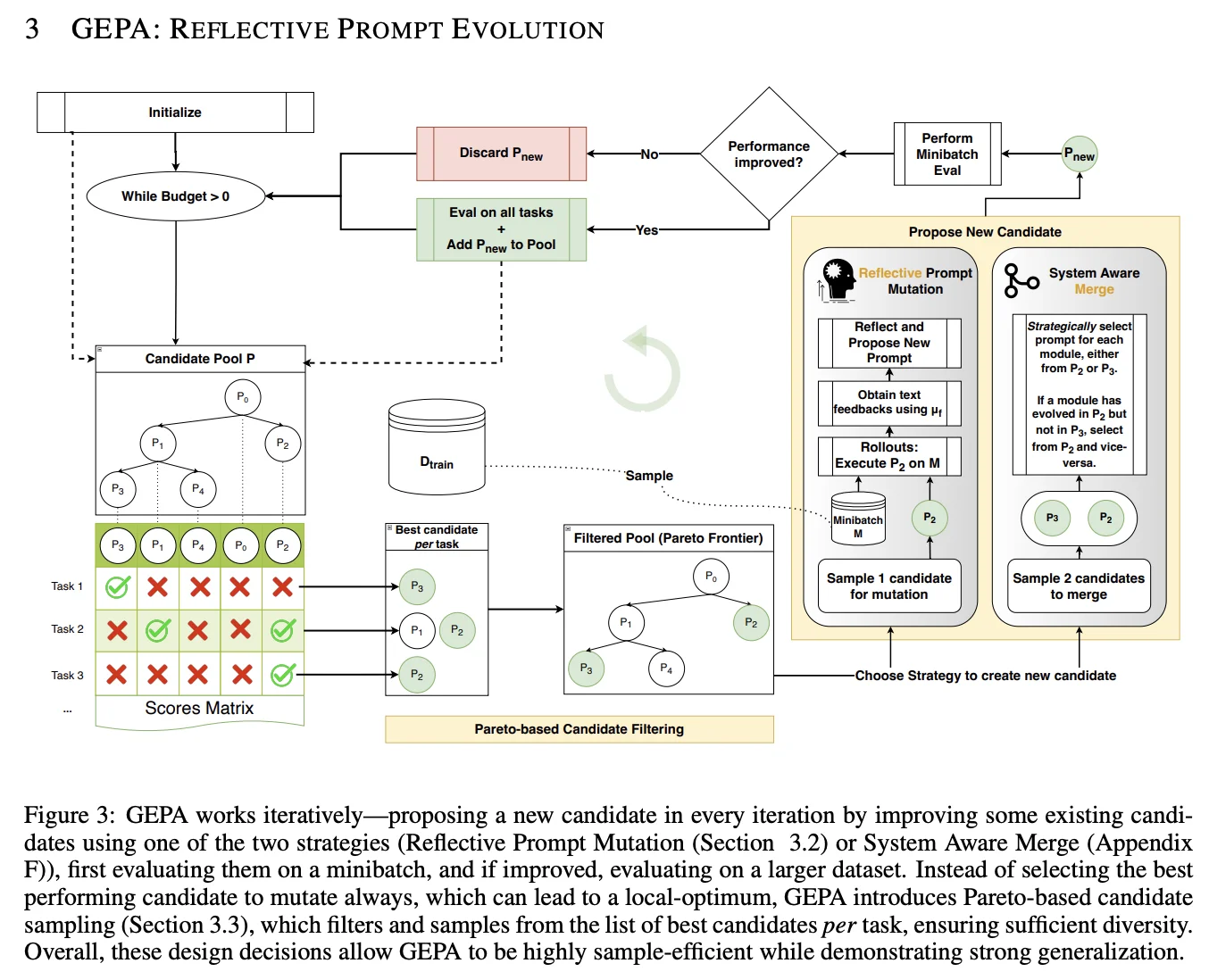

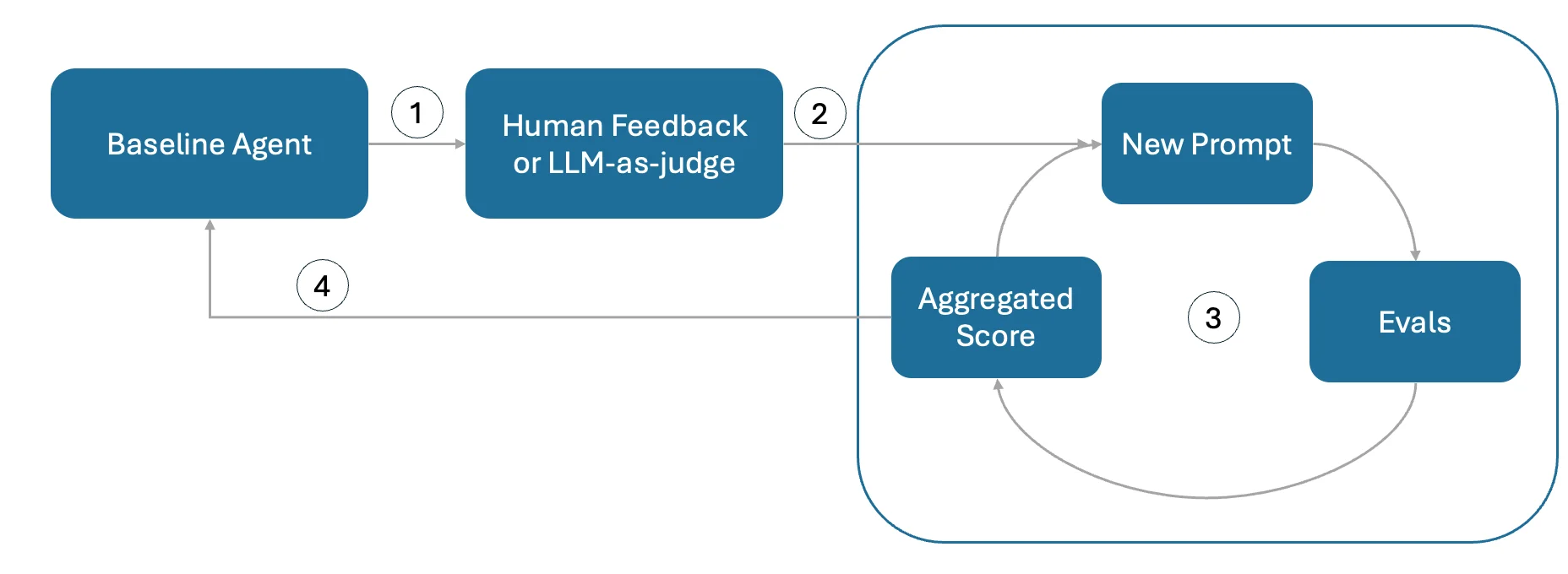

Evaluizer is an interface for evaluating and optimizing LLM prompts. It allows you to visualize outputs against datasets, manually annotate results, and run automated evaluations using both LLM judges and deterministic functions. It features GEPA (Genetic-Pareto), an optimization engine that iteratively evolves your prompts to maximize evaluation scores through reflective feedback loops.

For a final say on setup and observability, your choice of platform depends on what level of sophistication and funding is required. Need all the bells and whistles, running offline evals and online monitoring, plus a suite of tools? Tools like LangSmith have you covered for a fee. Looking to just get down and dirty with some quick annotations and experiments? Sounds like a job for pandas and Excel. Only care about integration and unit testing? Keep 'em in the tests folder. For all other custom workflows, take your favorite parts of all these setups and build something like Evaluizer.

Reaping What You Sow

Congratulations! If you've followed along at home, you've now effectively set up and defined your evaluation suite for your LLM-driven product. The investment in clearly defining and setting up evaluations can now lead to a multitude of benefits:

- You know what matters to your stakeholders

- You know how to measure what matters to your stakeholders

- You've become good friends with your hostage annotator

- You can automate and continually monitor performance that matters

- You can identify and mitigate failure modes that lead to low trust

No longer are your measurements based purely on vibes and brittle trial and error with prompt engineering, but are backed with quantitative data that you can confidently rely on and apply improvements with. Not only is this beneficial in the lifecycle of your product development, but it also helps to support the broader business metrics and goals that your application affects and builds trust with the end users.

But that's not all that you can benefit from- having evaluation metrics to optimize and annotated datasets available has secondary uses in a few burgeoning fields, particularly: algorithmic optimization and reinforcement learning.

GEPA: Reflective Prompt Evolution Can Outperform Reinforcement Learning

This pre-work rolls very conveniently into frameworks like DSPy (Declarative Self-Improving Python), which implement various algorithms to automate prompt refinement given a dataset and metrics to hill climb. They employ various techniques like automatic few-shot learning, MIPRO and GEPA to more consistently improve LLM performance and optimize prompts behind the scenes. The biggest barrier that I've seen to adopting DSPy has been the need for defined metrics and a dataset of 'training' examples to run through, which are (most often) not available when sitting down to create a new program. This is where all the work done above can come in, as we've laid the foundation to take advantage of these more automated systems.

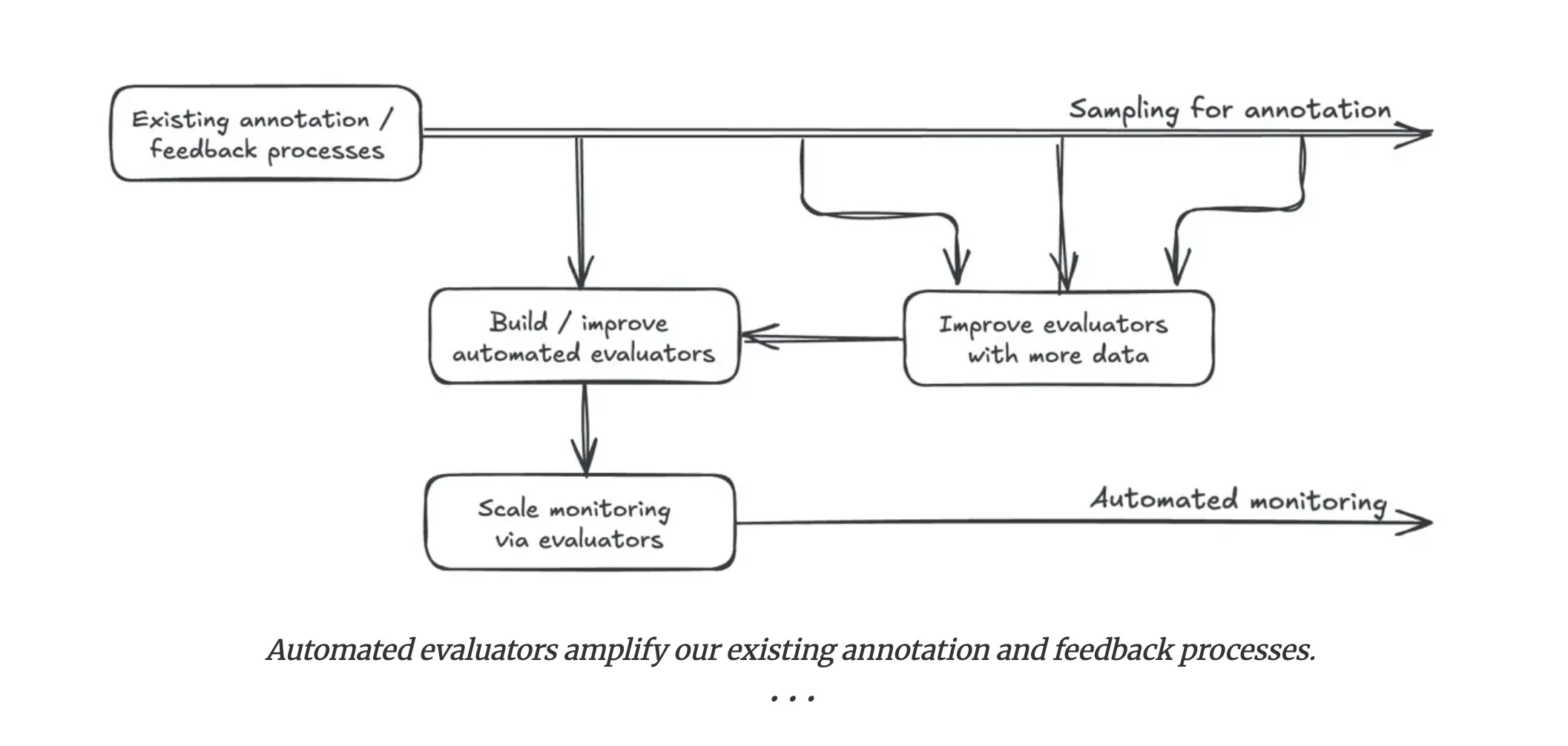

Self-Evolving Agents - A Cookbook for Autonomous Agent Retraining

Automated improvements based on metrics (without fine-tuning) have given rise to the idea of self-evolving agents, using either meta-prompting or the aforementioned algorithms programmatically based on online monitoring, triggering prompt updates when evals fall below defined thresholds. In my opinion, the use of metrics for automated evals is still relatively nascent. I can see it becoming more reliable as models and frameworks stabilize, as this idea extends our entire discussion by not just automating the evaluation but also the improvement process. In its current maturity I am more keeping tabs on how this is being applied and researched rather than directly implementing.

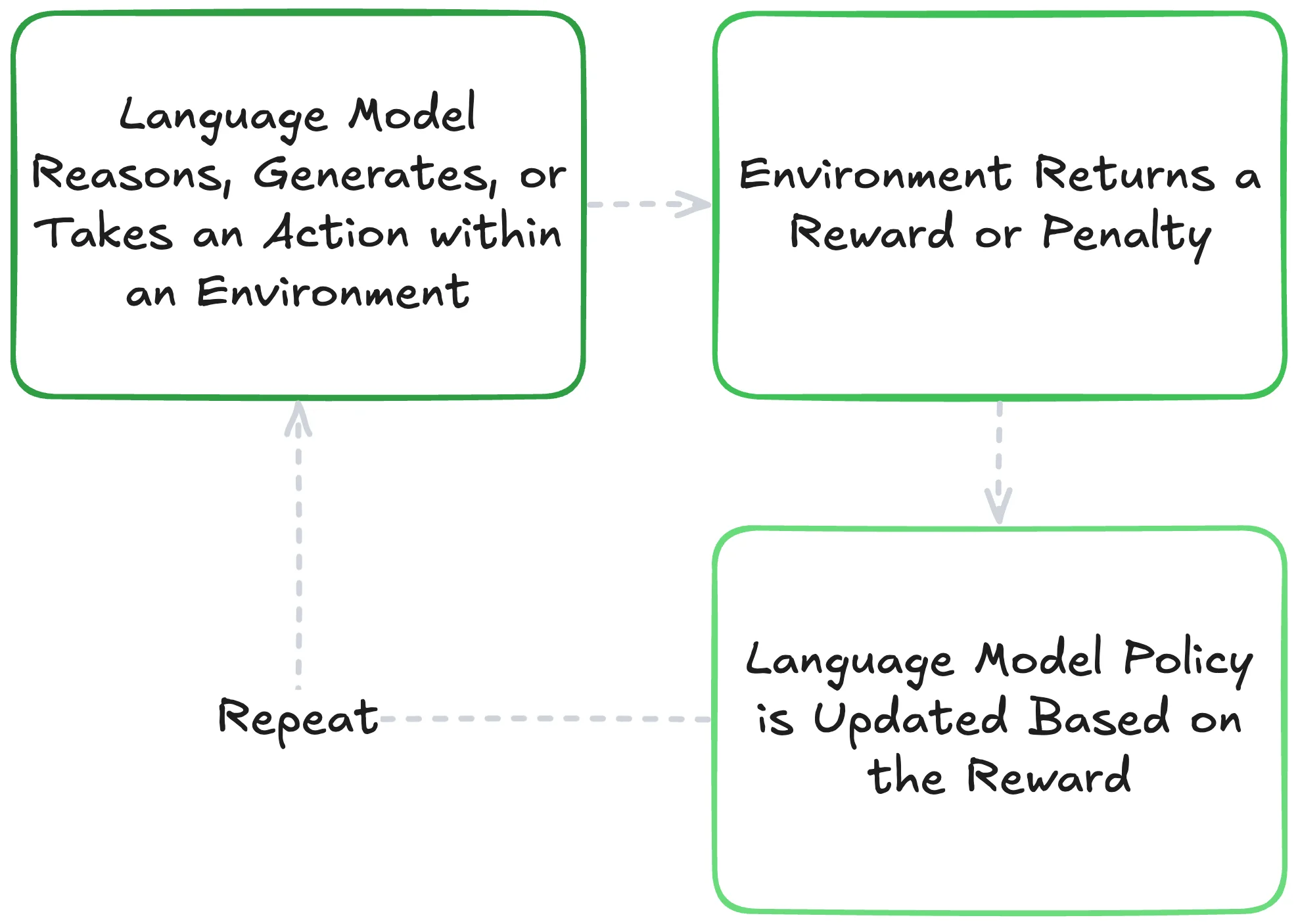

Secondly, our evaluations can also double as reward functions when fine-tuning LLMs with reinforcement learning. In this context, our product's main task and purpose would be the environment, and the evaluation metrics the reward functions. Through RL, we would iteratively sample our LLM (more officially referred to as the policy in RL), measure our rewards from the evals, and then use RL algorithms to tune the model towards a policy that maximizes our reward. Since our metric/reward combinations are, in theory, what we are trying to improve or maintain consistency of, this can directly instill the desired measured behavior into the model. As an even more enticing bonus, we can transfer the capabilities of a foundation model to an efficient small language model (SLM) given enough generated training examples or effective reward modeling. If you want to see the specifics of how I train LLMs using reinforcement learning, you can read more in my blog post Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards for LLMs.

Future Checklist

An important note about the continuous improvement of your LLM product: thinking back to the criteria drift phenomenon, I've seen this concept extend past just initial definitions and setup. As applications evolve, it's worth revisiting the individual steps and feedback collection exercises to ensure you're still in line with changing expectations and direction.

Over the few years that I've supported active AI projects, these two techniques have emerged as helpful:

Continual surveying and feedback collection: Even when making it easy to give feedback (i.e., a thumbs up/thumbs down on chat responses with a comment box), most users are not very inclined to spend time actively providing feedback- rather they just give up on using the product. Proactively soliciting feedback from your wider user base can help you discover new or underexplored failure modes, ideas for additional features, and form a baseline for user satisfaction. I've found these styles of engagement to help with general trust building and setting future direction.

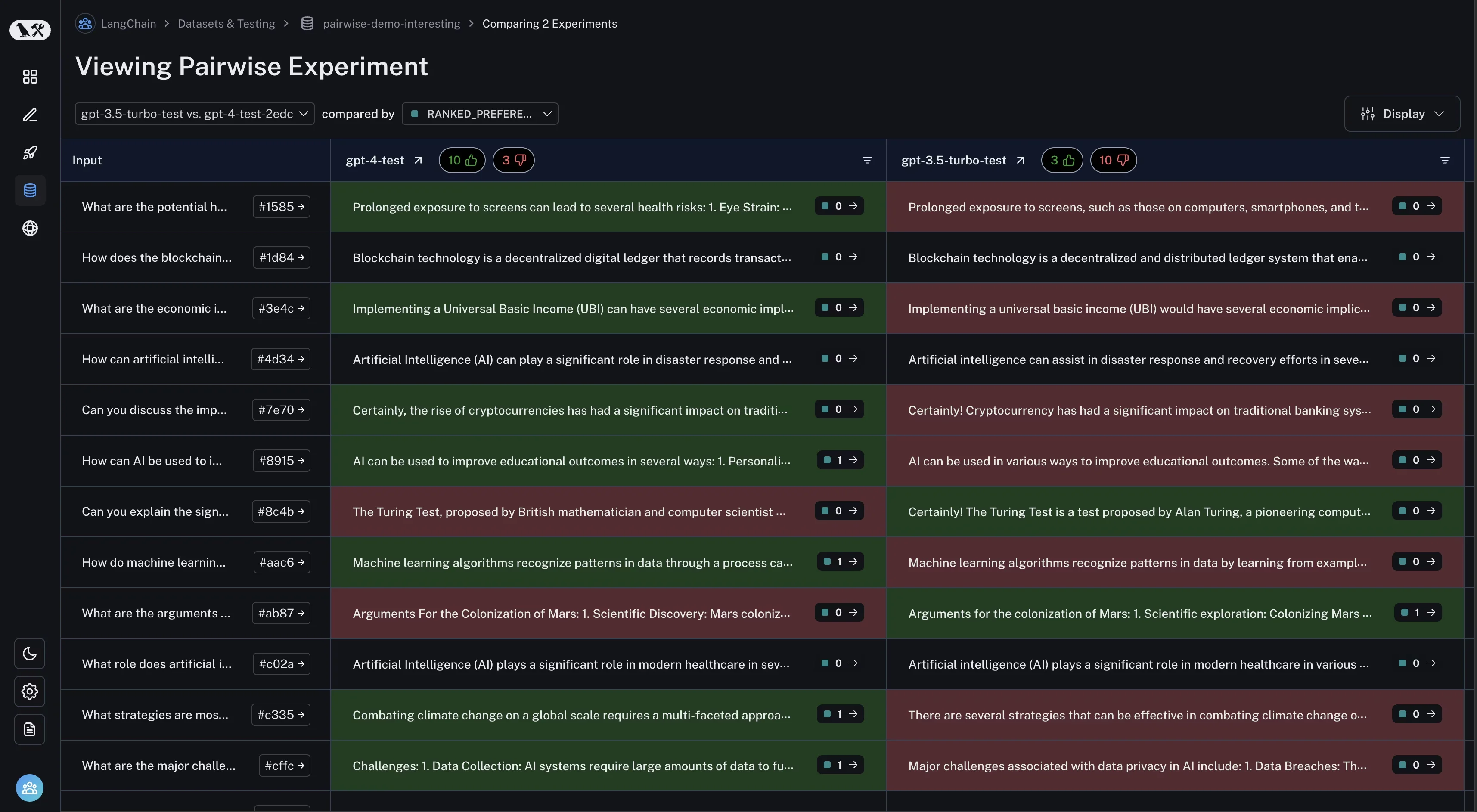

How to run a pairwise evaluation

Version Testing: As your products and metrics change over time with features and direction, some of the same approaches to evaluating can be applied not just at an individual performance level but across product versions. Rather than looking at one single output, we can run pairwise experiments. Using the same datasets of inputs and outputs that were generated from an older version, then run these through your updated system and directly pit the old vs new output against each other. Once again, this is most effectively done by employing a willing SME subject to compare the two and assign their preference. If you've got a highly sophisticated setup, it's even possible to align an LLM judge on pairwise scoring with enough examples!

Is It Worth It?

Keeping up with the evolving needs of your users, surfacing domain-specific metrics, working with SMEs, and applying these carefully planned out evaluation frameworks all assist in guiding effective and measurable improvements to your system while building trust and buy-in from your users. Through engaging early with SMEs to discover failure modes and judge outputs, we can align our eval strategy directly to what would give us the most relevant improvement path. This can be further scaled using aligned LLMs as judges and related test functions, enabling automated scoring, leading to direct insights into whether our product is performing in the expected manner, and whether a change actually leads to improvement or not.

Whether you go through the rigor of setting up full evaluation suites or not, understanding the purpose and benefit of application-specific evals will help you make more informed decisions on how to improve your AI product.

Special thanks to Hamel Husain, Eugene Yan, and Shreya Shankar whose blogs heavily inspired the content of this blog and its application to what I do.